My decision to watch Ken Russell’s 1971 film The Devils was purely by chance. In an effort to avoid getting stuck in indecision paralysis, as has been the case over the last five or six years, I found the first film that I was unfamiliar with on Criterion Channel, and I went for it. And boy did that blind decision pay off.

The film starts out, after some on-screen commentary as to the authenticity of the subject matter, with a Victorian-era stage setting. I can’t help but think that Terry Gilliam took inspiration of this scene, particularly with Time Bandits, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, & Adventures of Baron Munchausen. There are crafted and painted waves moving back and forth across the view in front of a crescent moon stage prop. There is a mocking & playful sense of divinity proclaimed by horns as the King of France rises into view, painted and made-up in drag with naught but cockleshells as a top and bikini. While most of us are familiar with Gilliam’s joyful and triumphant portrayal of the stage, Russell’s portrayal is dark and auspiciously malevolent.

I love when film makers refer to the making of a stage/screen production, as it tends to proclaim the work as a practice in self-awareness. It also gently pokes a hole in the fourth wall, letting the audience know that we are all both watching the play, as well as a part of it, in the ever circling debate of which came first, art or life. So while Russell pleads with his audience to keep in mind that these events are of factual and historical significance, we are to be kept in rapt awareness that this is indeed a work of art.

Yet this scene is punctuated by the sex & violence that follows and carries through the rest of film.

But it is here where all and any playfulness ends, as the next scene opens up with a moldy corpse with maggots having made nest inside the remains and pour out as the corpse spins on a torture wheel in the afternoon breeze. And the film continues its reign of horror in a similar fashion throughout the reel.

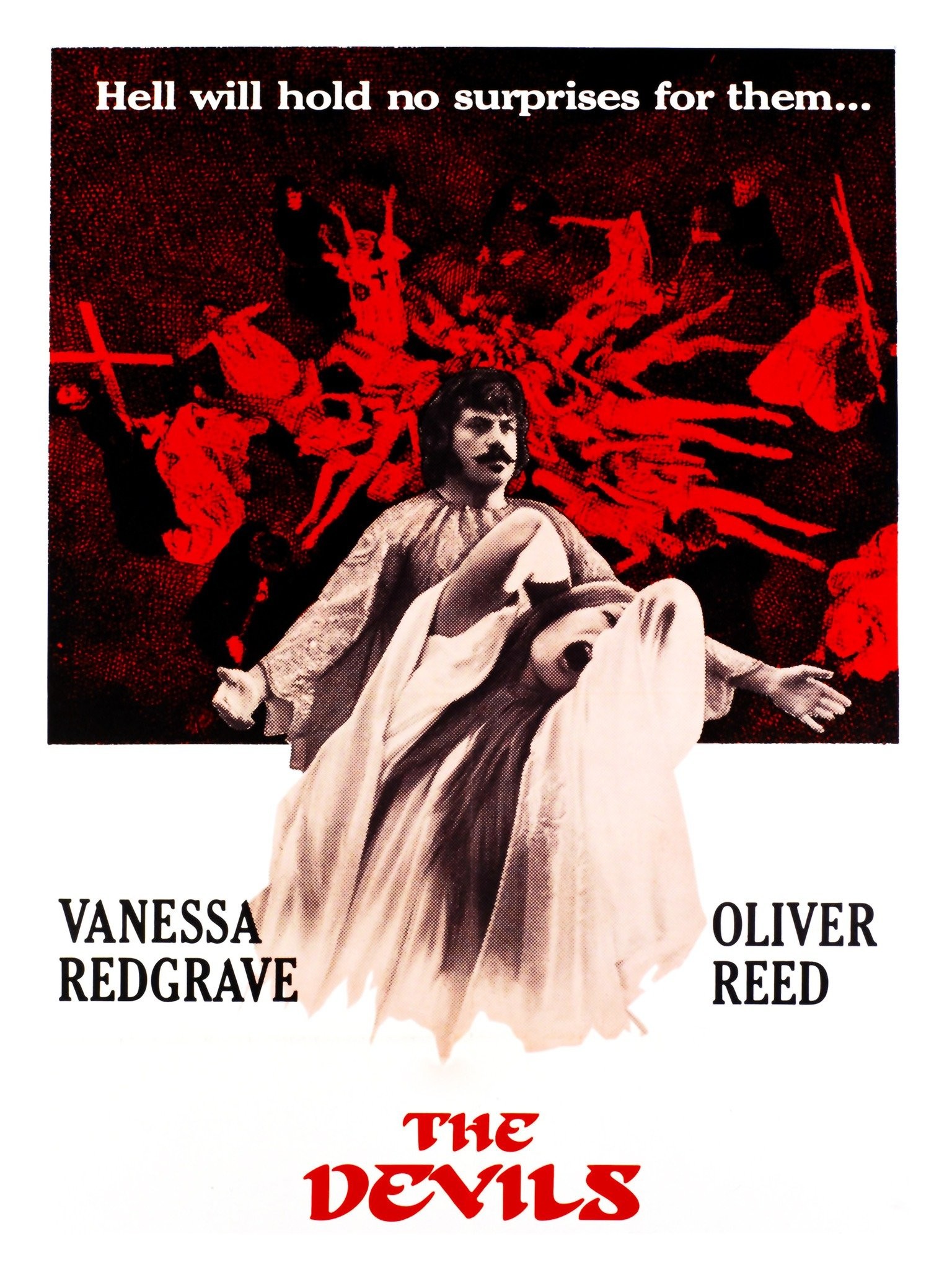

The plot pivots around the adulterous behaviors of the philandering priest, Father Grandier played by Oliver Reed and the lustful reactions of the nuns at the local Ursuline convent. Mother Superior, a hunchbacked Sister Jeanne des Agnes, played brilliantly by Vanessa Redgrave, takes a centrally supporting role. The antagonist of the film is played by the lurking unholy matrimony of church and state between Cardinal Richelieu and Louis XIII. Long story short, the nuns lust after a priest, as he defends the local town from an onslaught from a King influenced by a power-hungry cardinal. The abbess of the nunnery falls in lust with the priest, displaying erratic behavior, which later culminates in an exorcism, described by Aldous Huxley in his novelized version of the story The Devils of Loudun, as “a rape in a public lavatory.”

A modern Feminist criticism of the film might focus on the glaring misogyny of portraying nuns in the centuries old women-as-Judas role, all the while the very male church is more than happy to play Pontius Pilate, hoping to get rid of the problematic priest who stands in the way of the Catholic Church and its grand designs. A Marxist criticism would point a spot light at the obvious malevolent nature of both church and state, the blatant oppressive nature of both, and terrifying possible reality of life in a theocratic society. While I personally agree with both criticisms, what I find most compelling is the multi-level abstraction of humanity. Grandier is clearly very human, yet still oddly capable of some level piety and compassion, even though many of his actions, at least early in the film speak to a wildly different conclusion. However, I might suggest that this is partly the point—the dualistic nature of humanity.

In my personal life, I often talk about the “adorableness” of humanity, how it is our emotionally fragile nature that makes us perpetually children. Granted this perspective conveniently leaves out the more disgusting violent and oppressive nature of the everything we touch, but I speak more on a micro-personal level. I would often point out how when we watch children learn to walk. They take their first couple of steps, get over confident and decide to make a go at running. What happens? We fall down, bump our heads and work ourselves into a frenzied frustration. I argue that we don’t really change much from the stumbling fool we emblematize in our infancy. And it is through this lens from which I have learned to develop a humorous compassion for my fellow humans. We continue to fall, bump our proverbial heads, and get pissed.

There is something intrinsically human about most of The Devils characters, primarily Grandier and Sister Jeanne. To see such caricatured lust in the hearts of people of the cloth only reminds me that the so-called “holy” are also just humans, with human needs, and human desires. And we can lay heaps of judgement upon them both, as they are both worthy of revulsion. But is it not this same human lust and desire that makes them worthy of empathy. Because in the end, the state is still coming for your blood, and the church is still coming for your soul. And in the end, regardless of our intentions, can just as easily be burned alive by the powers that be. Grandier was sexual predator, but in the end, he is put to death. Not for his human traits, but that he decided to stand in the way power.